An essay for ENVS459 Implementing and Managing Change. It discusses the main features of the planning system in Massachusetts. The essay received an 86, a high distinction. Written in June 2017.

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts’ planning system reflects a balance between a legacy of local control and more recent state efforts to guide development in its 351 municipalities. State law establishes a framework for local planning in Part I Title VII Chapter 40A – Zoning, of the Massachusetts General Laws (MGL) (Sardella, 2016; DHCD, 2016). The framework sets the minimum requirements that local planning and zoning boards must follow, with the state offering financial incentives for towns to voluntarily adopt other planning mechanisms. Examples of such mechanisms include Business Improvement Districts (Chapter 40O), Smart Growth Zoning (Chapter 40R) and Community Preservation (Chapter 44B). One notable exception to local choice is Chapter 40B—Regional Planning, which extends state control over the siting and approval of affordable housing. A stalled zoning reform bill—to overhaul section 40A—is arguably another example of the state attempting to exert control over local planning (Sardella, 2016). This brief delves into those issues and the key features of planning in Massachusetts, but begins by providing some important context.

Massachusetts is one of the 13 original states of the United States, with its founding dating to 1620 (Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2017). Today, over 6.8 million residents live in a state that US News & World Report ranks the best in the nation, with particular credit for its healthcare and education provision (US Census Bureau, 2016; Tilak, 2017). In 2016, the economy outpaced the national growth rate and, as of April 2017, the unemployment rate is 3.9%, which is below the national average of 4.4% (Swasey, 2017; BLS, 2017). The state government is, in general, seeking environmentally sustainable development. In particular, the state has released a climate change plan that calls for new zoning legislation and relies, in part, on municipalities pursuing smart growth to reduce transport-related emissions (EEA, 2015). However, the state faces a housing affordability challenge. The National Low-Income Housing Coalition (2016) ranks Massachusetts the seventh least affordable state in the country, noting that people earning minimum wage would need to work, on average, 83 hours per week to rent a one-bedroom apartment. In addition, 50% of respondents to a Boston Globe survey cited housing costs as a major factor in their decision to leave the state (Bluestone, 2006). However, improving housing affordability conditions through the planning system is difficult because of the emphasis on local control.

The principle of local control is sacrosanct in Massachusetts, as embodied by the peculiar use of town meeting-style government in the state’s 295 towns (whereas cities have an elected mayor and representative council) (Crawford, 2013). In general, this form of government enables all adults to attend meetings to ‘debate and vote on municipal decisions’, including planning matters (Karki, 2014, p.250). This tradition of hyperlocal democracy translates into a concept called Home Rule, which in practice means that cities and towns ‘wield a wide range of land use and regulatory powers’ with planning ‘mainly concentrated at the municipality level’ (Fisher, 2012; Wang, 2014, p.75).

At the municipal level, the local planning board and the zoning board of appeals (ZBA) have the primary responsibility for planning (see: Table 1). Each municipality has an elected or appointed planning board, which prepares a master plan that sets development goals, covering topics such as land use, housing and open space (CPTC, 2013). The MGL specify the elements that must be part of the plan, but defer to the board to simply prepare a plan ‘from time to time’ and characterise the document as advisory only (MGL I.VII.41§81D; CPTC, 2013). The gap between plans can be large. For example, Boston is only now preparing a new comprehensive plan—for the first time since 1965 (Imagine Boston, 2017). In contrast, the crux of the local planning system is embedded in zoning, which ‘defines the rules governing what and where people and institutions can and cannot build and operate’ (Hirt, 2015, p.3).

Table 1: Key Responsibilities of the Planning Board and Zoning Board of Appeals

Source: author’s analysis of MGL I.VII.41§81D-GG and MGL I.VII.40A§13, the table lists the responsibilities of the planning board and zoning board of appeals.

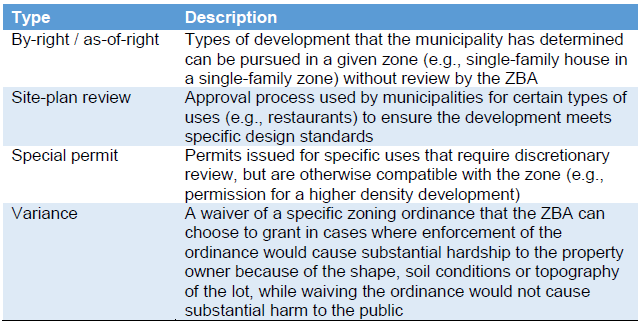

Zoning is a legal instrument that permits or prevents different types of construction, called ‘uses’ (e.g., housing) according to one of four circumstances (see: Table 2). Zoning laws, called ordinances, are presented with text and maps to specify where particular uses are permissible (CPTC, 2013). The local planning board is responsible for reviewing, proposing and conducting hearings on zoning ordinances, while the ZBA interprets the ordinances in cases that are not by-right (CPTC, 2013). Neither the planning board nor the ZBA can unilaterally adopt or amend an ordinance. Instead, adoption rests on a two-thirds majority vote of the city council or town meeting (MGL I.VII.40A§5). Still, municipalities are not wholly unconstrained in adopting zoning ordinances.

Table 2: Four Types of Zoning Permissions

Source: author’s analysis of the MGL I.VII.40A and the Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs Zoning Decisions toolkit, this table describes the four types of zoning permissions.

As mentioned previously, Chapter 40A establishes the framework for zoning ordinances. Specifically, the Chapter limits the power of municipalities to regulate aspects of certain types of uses, such as farming, religious and educational buildings and solar energy systems (MGL I.VII.40A§3). Imposing these limits on local power is frequently controversial. For example, the state adopted the solar provision in the 1980s, but ambiguity in the law has led to recent conflicts in some communities about whether it only applies to small-scale or all types of systems, including multi-acre farms (Department of Energy Resources, 2014; O’Neil, 2012). Towns can adopt ordinances to apply reasonable limits, but the recent decline in the price of solar panels and two-thirds voting barrier to new ordinances has left some communities unprepared (Zollshan, 2017). Chapter 40A also describes various administrative matters, including the types of special permits that municipalities can choose to provide, public notification and hearing requirements for zoning changes, protections for grandfathered buildings (i.e., those predating the ordinance) and penalties for non-compliant developers (MGL I.VII.40A). However, within that framework, the individual community retains the power to define and locate the specific zones, with some municipalities excluding certain types of development entirely (Hirt, 2015; Colby, 2010).

In many parts of the state, regional planning commissions operate as an intermediate layer between local and state planning. Regional planning, however, is entirely voluntary, with municipalities needing to vote to create a regional planning district (MGL I.VII.40B). To date, 12 such commissions exist (APA-MA, 2017). Once created, commissions prepare non-binding plans that feature ‘recommendations for the physical, social, governmental or economic improvement of the district’ (MGL I.VII.40B§5). Commissions range in size from the 6 communities on the island of Martha’s Vineyard to the 101 communities in the Metropolitan Area Planning Council that encompasses Greater Boston.

At the state-level, the government has three branches: the executive—headed by a governor, Supreme Judicial Court and the General Court—its bicameral legislature. The Democratic Party has long dominated the Massachusetts General Court. In its 190th session (2017-2018), the Senate has 34 Democrats and 6 Republicans and the House of Representatives has 126 and 34, respectively (General Court, 2017a; 2017b). In the legislature, several committees have jurisdiction over planning, including the House and Senate Committees on Ways and Means and the Joint Committees on Housing, Transportation and Community Development and Small Business. Topics receiving attention this session include smart growth (S.80, H.128), affordable housing (S.90, S.91), accessory apartments (H.127) and community benefit districts[1] (S.82, H.1971). Although Democrats have supermajorities in both houses, planning does not match party affiliation. The ongoing debate about the Chapter 40A zoning reform is illustrative.

In 2016, the Senate passed a comprehensive zoning reform bill, which, if enacted, would have been the first such law since 1975 (Eldridge and Leroux, 2011). The bill would have imposed a series of new requirements on communities, including adopting inclusionary zoning, developing local plans that align with sustainable development principles, establishing districts for multi-family housing and reducing the voting threshold for many planning matters to simple majorities (Wolf, 2016). The objective was to modernise the system by requiring municipalities to zone for a wider variety of housing types and to enable more compact development as a way to promote environmental sustainability (Eldridge and Leroux, 2011). During debate on the bill, Democratic Senator Ives said that the state ‘can’t plan with 351 communities always doing their own thing’ arguing that the bill would provide ‘a state perspective and state plan’ to guide development (Statehouse News Service, 2016).

A number of organisations supported the bill, including the American Planning Association’s Massachusetts Chapter, the Environmental League of Massachusetts and the Massachusetts Municipal Lawyers Association. However, detractors called it a ‘land use lasagne’ and a ‘maze’ for communities to figure out (Statehouse News Service, 2016). Further, the Massachusetts Municipal Association (MMA) opposed the bill and viewed it as a legal gift for developers looking to ‘pre-empt local decision-making’ (MMA, 2016). The Senate passed the bill 23-15, but nine Democratic Senators joined the six Republicans to oppose the legislation and the bill died in the heavily Democratic House without receiving a committee or floor vote (Young, 2016). Whether the bill can pass in this current session remains to be seen (it has been reintroduced), although more targeted legislation (e.g., creating voluntary incentives for starter home districts) advanced before the last session ended (Levey, 2016).

The executive branch is responsible for implementing the planning legislation passed by the General Court and endorsed by the governor. Despite Democratic supermajorities in the legislature, Massachusetts voters frequently elect Republican governors. Currently, Charlie Baker, a Republican, is serving his first term, having assumed office in January 2015. Baker succeeded Deval Patrick, a Democrat, who had succeeded Mitt Romney, a Republican, in January 2007. Nearly all state bodies involved in planning fall under the Office of the Governor with one exception—the Historical Commission, which is part of the Office of the Secretary (see: Figure 1). Broadly, the bodies fall into six categories: general land use and housing, transport, agriculture, parks and recreation, historic preservation and coastal and marine planning. Each body issues regulations to implement the legislation passed by the legislature, with the public given an opportunity to provide feedback before the regulations are finalised. For example, the Department of Housing and Community Development’s (DHCD) Division of Community Services is responsible for issuing guidance and regulations related to zoning, business improvement districts, smart growth districts, compact neighbourhoods, urban regeneration and more (EOHED, 2017a). However, recent activities in Chapter 40R, 44B and 40B indicate that housing is a primary focus.

In 2004, the legislature passed the Chapter 40R Smart Growth Zoning Overlay District Act. The goal was to encourage towns to zone for dense residential or mixed-used neighbourhoods (including affordable housing) near transit or existing town centres (EOHED, 2017b). As with many features of state-level planning in Massachusetts, Chapter 40R is a voluntary incentive programme that offers communities a lump sum payment depending on the size of the zone plus money for each home built (Fierro, 2016). As of March 2016, only 10% of communities had smart growth districts approved or under review, averaging 384 housing units built or planned per district (EOHED, 2016). Such limited participation in the programme underscores the weakness of using voluntary initiatives to drive different local planning behaviours. Critics have also noted that most truly smart growth elements are optional and that density standards are only for housing, so they argue the Act is primarily a mechanism to boost housing supply (Wang, 2014; Karki, 2014). Recent events support their arguments. In 2016, the legislature decided to expand the smart growth programme to include incentive payments for districts featuring single-family starter homes (Fierro, 2016).

Figure 1: Organisational Chart of State level Offices Involved with Planning

Another vehicle for housing creation is Chapter 44B – the Community Preservation Act (CPA). The state created the voluntary programme in 2000, which allows residents to vote for a property tax surcharge to fund three initiatives: building affordable housing, preserving open space and funding historic preservation (CPC, 2017). The state provides matching dollars from a trust fund endowed with a surcharge on property sales state-wide (DiCara and Nicholson, 2015). The law requires 10% of the funding to go to each initiative, with the remaining 70% able to be spent on those initiatives or recreation (Herndon, 2017). In 2016, Bostonians adopted the CPA in a referendum, with backers calling on the city council to earmark most funds raised for affordable housing (Herndon, 2017). Demand for affordable housing is high, with 40,000 families on Boston’s affordable housing waitlist vying for only 15,000 subsidised homes (Johnston, 2014). Boston joined the nearly half of Massachusetts communities that have adopted the CPA, but critics argue the Act transfers money raised from property sales in poorer communities that cannot afford the surcharge to wealthier ones that can (CPC, 2017; DiCara and Nicholson, 2015; Sherman and Luberoff, 2007). Further challenges are on the horizon for the CPA, as the increasing number of communities participating in the programme has drained the trust fund, a problem that the state postponed via a one-time transfer of funds from its budget surplus (Ring, 2013).

In contrast to the voluntary programmes, DHCD also administers a mandatory affordable housing programme under Chapter 40B that has been a lightning rod for Home Rule advocates. Created in 1969, the programme enables developers to override local zoning if less than 10% of a community’s housing stock qualifies as affordable (Fisher and Marantz, 2015). The Act created the state Housing Appeals Committee, which, with few exceptions, can compel a ZBA to approve the application if at least 20% of the new homes would be affordable (Hananel, 2014). The controversial instrument to supersede local decision-making has achieved some noticeable results. As of 2010, 15% of communities had met the 10% threshold, an increase from 1% in 1969 (Hananel, 2014). In addition, the programme has facilitated construction of 60,000 units, with over 54% reserved for lower income individuals (Hananel, 2014). However, critics argue developers can ‘profit above and beyond’ the limit set for 40B developments and that oversight is lacking to ensure only low-income individuals access affordable units (Sullivan, 2012). A measure to repeal the programme was on the November 2010 ballot, but voters defeated it 54% to 39% (Secretary of Massachusetts, 2017). Still, reform may be likely. Supporters and detractors of zoning reform bills expressed a shared desire to overhaul 40B in future legislation (Statehouse News Service, 2016).

Ultimately, Chapter 40B is an anomaly compared to a system of state-level planning that relies on voluntary initiatives, like 40R and 44B, to achieve development goals. Still, these voluntary initiatives have achieved mixed results in spurring community action. Relatively few smart growth districts have been built. CPA adoption is far higher, but if funds are primarily used for historic preservation and to conserve open space, then they may exacerbate the housing shortage and increase inequality among communities. Recent attempts to centralise planning power, as embodied by the zoning reform bill, have stalled in the face of the deeply embedded tradition of Home Rule. Municipalities appear to tolerate a framework for zoning, but requiring certain zones and types of developments may remain a step too far for the near future. Although many social, environmental and economic indicators in Massachusetts are positive, housing affordability remains a thorny issue. Whether or not the issue provokes serious changes to planning remains to be seen.

Bibliography

American Planning Association Massachusetts Chapter. (2017). Massachusetts Regional Planning Agencies. Available at: http://www.apa-ma.org/resources/massachusetts-regional-planning-agencies (Accessed 26 May 2017).

Bluestone, B. (2006). ‘Sustaining the Mass economy: Housing costs, population dynamics, and employment’, draft report prepared for the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston’s Conference on Housing and the Economy in Boston, 22 May. Available at: http://www.massgrowth.net/writable/resources/document/sustaining_the_mass_economy.pdf (Accessed 23 May 2017).

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2017). April: State employment and unemployment summary. Washington, DC: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Citizen Planner Training Collaborative. (2013). Roles and responsibilities of planning and zoning boards: Part I. Boston: Citizen Planner Training Collaborative. Available at: http://masscptc.org/documents/conference-docs/2013/Roles%20&%20responsibilities-Part%20I%203_16_13.pdf (Accessed 25 May 2017).

Colby, E. (2010). ‘Supporters defend affordable-housing legislation as referendum heads to ballot’, Brookline TAB, 1 March. Available at: http://brookline.wickedlocal.com/x661205997/Supporters-defend-affordable-housing-legislation-as-referendum-heads-to-ballot (Accessed 23 May 2017).

Community Preservation Coalition. (2017). CPA: An overview. Available at: http://www.communitypreservation.org/content/cpa-overview (Accessed 24 May 2017).

Crawford, A. (2013). ‘For the people, by the people’, Slate, 22 May. Available at: http://www.slate.com/articles/news_and_politics/politics/2013/05/new_england_town_halls_these_experiments_in_direct_democracy_do_a_far_better.html (Accessed 25 May 2017).

Department of Energy Resources. (2014). Policy guidance for regulating solar energy systems. Boston: Massachusetts Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs. Available at: http://masoa.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/model-solar-zoning-guidance.pdf (Accessed 23 May 2017).

Department of Housing and Community Development. (2016). The zoning act. Boston: Department of Housing and Community Development. Available at: http://www.mass.gov/hed/docs/dhcd/cd/zoning/zoningact.pdf (Accessed 26 May 2017).

DiCara, L.S. and Nicholson, M. (2015). ‘The downsides of Prop. 2 ½ and Community Preservation Act’, CommonWealth, 17 December. Available at: https://commonwealthmagazine.org/economy/downsides-of-prop-2%C2%BD-and-community-preservation-act/ (Accessed 24 May 2017).

Eldridge, J. and Leroux, A. (2011). ‘Eldrige and Leroux: Time to get smart about growth’, Metrowest Daily News, 6 November. Available at: http://ma-smartgrowth.org/wp-content/uploads/issues_111212_zoning-time-to-get-smart.pdf (Accessed 23 May 2017).

Energy and Environmental Affairs. (2015). Massachusetts Clean Energy and Climate Plan for 2020. Boston: Executive Office for Energy and Environmental Affairs.

Executive Office of Housing and Economic Development. (2016). Smart growth zoning districts approved, eligible, or under review or proposed in Massachusetts. Available at: http://www.mass.gov/hed/docs/dhcd/cd/ch40r/40ractivity.pdf (Accessed 25 May 2017).

Executive Office of Housing and Economic Development. (2017a). Community Planning. Available at: http://www.mass.gov/hed/community/planning/ (Accessed 25 May 2017).

Executive Office of Housing and Economic Development. (2017b). Chapter 40 R. Available at: http://www.mass.gov/hed/community/planning/chapter-40-r.html (Accessed 23 May 2017).

Executive Office of Housing and Economic Development. (2017c). Zoning decisions. Smart Growth / Smart Energy Toolkit. Available at: http://www.mass.gov/envir/smart_growth_toolkit/pages/mod-zoning.html (Accessed 26 May 2017).

Fierro III, B. (2016). ‘Legislature approves zoning changes, new housing program’, Massachusetts Lawyers Weekly, 26 September. Available at: http://www.lynchfierro.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Fierro_LegislatureApprovesZoningChanges.pdf (Accessed 23 May 2017).

Fisher, L.M. (2012). ‘State intervention in local land use decision making: The case of Massachusetts’, Real Estate Economics, 41(2), pp. 418-447.

Fisher, L.M., and Marantz, N.J. (2015). ‘Can state law combat exclusionary zoning? Evidence from Massachusetts’, Urban Studies, 52(6), pp. 1071-1089.

Hananel, R. (2014). ‘Can centralization, decentralization and welfare go together? The case of Massachusetts affordable housing policy’, Urban Studies, 51(12), pp. 2487-2502.

Herndon, A.W. (2017). ‘Affordable housing advocates crave bigger slice of CPA revenue’, Boston Globe, 11 February. Available at: https://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/2017/02/11/affordable-housing-advocates-push-for-bigger-slice-cpa-revenue/nIFvMDENCtvWsOVJGNjhPN/story.html (Accessed 26 May 2017).

Hirt, S. (2015). Zoned in the USA: The origins and implications of American land-use regulation. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Imagine Boston 2030. (2017). About. Available at: https://imagine.boston.gov/about/ (Accessed 1 June 2017).

Johnston, K. (2014). ‘Demand soars for affordable housing in Boston area’, Boston Globe, 28 November. Available at: https://www.bostonglobe.com/business/2014/11/28/demand-for-affordable-housing-soars/hCb4RSkLTbpqdMJR1eCYTI/story.html (Accessed 1 June 2017).

Karki, T.K. (2015). ‘Mandatory versus incentive-based state zoning reform policies for affordable housing in the United States: A comparative assessment’, Housing Policy Debate, 25(2), pp. 234-262.

Levey, B. (2016). ‘Recent changes to the Massachusetts Zoning Act and Smart Growth Zoning’, Beveridge & Diamond PC, 27 September. Available at: http://www.bdlaw.com/news-1967.html (Accessed 23 May 2017).

Massachusetts General Laws. Part I. Title VII. Chapter 40 A. Zoning. Available at: https://malegislature.gov/Laws/GeneralLaws/PartI/TitleVII/Chapter40A (Accessed 25 May 2017).

Massachusetts General Laws. Part I. Title VII. Chapter 40A. Section 3. Subjects which zoning may not regulate; exemptions; public hearings; temporary manufactured home residences. Available at: https://malegislature.gov/Laws/GeneralLaws/PartI/TitleVII/Chapter40A/Section3 (Accessed 25 May 2017).

Massachusetts General Laws. Part I. Title VII. Chapter 40 A. Section 5. Adoption or change of zoning ordinances or by-laws; procedure. Available at: https://malegislature.gov/Laws/GeneralLaws/PartI/TitleVII/Chapter40A/Section5 (Accessed 25 May 2017).

Massachusetts General Laws. Part I. Title VII. Chapter 40A. Section 13. Zoning administrators; appointment; powers and duties. Available at: https://malegislature.gov/Laws/GeneralLaws/PartI/TitleVII/Chapter40A/Section13 (Accessed 25 May 2017).

Massachusetts General Laws. Part I. Title VII. Chapter 40B. Regional Planning. Available at: https://malegislature.gov/Laws/GeneralLaws/PartI/TitleVII/Chapter40B (Accessed 25 May 2017).

Massachusetts General Laws. Part I. Title VII. Chapter 40B. Section 5. Powers and duties; reports. Available at: https://malegislature.gov/Laws/GeneralLaws/PartI/TitleVII/Chapter40B/Section5 (Accessed 25 May 2017).

Massachusetts General Laws. Part I. Title VII. Chapter 41. Section 81D. Planning board; establishment; membership; tenure; vacancies. Available at: https://malegislature.gov/Laws/GeneralLaws/PartI/TitleVII/Chapter41/Section81A (Accessed 25 May 2017).

Massachusetts Municipal Association. (2016). ‘Senate leaders advance bill to make major changes in housing and zoning laws’, legislative alert, 2 June. Available at: http://www.amherstma.gov/DocumentCenter/View/35112 (Accessed 23 May 2017).

National Low Income Housing Coalition. (2016). Out of reach 2016: Massachusetts. Available at: http://nlihc.org/oor/massachusetts (Accessed 24 May 2017).

Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2017). Massachusetts Bay Colony. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/place/Massachusetts-Bay-Colony (Accessed 24 May 2017).

General Court of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. (2017a). Senate Members. Available at: https://malegislature.gov/People/Senate (Accessed 24 May 2017).

General Court of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. (2017b). House Members. Available at: https://malegislature.gov/Legislators/Members/House (Accessed 24 May 2017).

Ring, D. (2013). ‘Community preservation funds in Massachusetts bolstered by $25 million from state budget surplus’, Mass Live, 1 December. Available at: http://www.masslive.com/politics/index.ssf/2013/12/state_preservation_funds_in_ma.html (Accessed 24 May 2017).

Sardella, M. (2016). ‘Zoning bill worrisome’, The Wakefield Daily Item, 15 July. Available at: http://wp.localheadlinenews.com/?p=26886 (Accessed 23 May 2017).

Secretary of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. (2017). Statewide ballot questions – statistics by year: 1919 – 2016. Available at: http://www.sec.state.ma.us/ele/elebalm/balmresults.html (Accessed 23 May 2017).

Sherman, R. and Luberoff, D. (2007). ‘The Massachusetts Community Preservation Act: Who benefits, who pays?’, Public Finance, July. Available at: https://www.hks.harvard.edu/content/download/68598/1247202/version/1/file/cpa_final.pdf (Accessed 24 May 2017).

Statehouse News Service. (2016). ‘Senate session – Thursday, June 9, 2016’. Available at: http://www.statehousenews.com/content/live/2016/Senate06-09.html (Accessed 23 May 2017).

Sullivan, G. (2012). Oversight of chapter 40B affordable housing rentals, letter to Aaron Gornstein, Undersecretary, Department of Housing and Community Development. Boston: Inspector General of Massachusetts. Available at: http://www.mass.gov/ig/publications/reports-and-recommendations/chapter-40b-publications/oversight-of-chapter-40b-affordable-housing-rentals-july-2012.pdf (Accessed 23 May 2017).

Swasey, B. (2017). ‘Mass. Economic growth slightly outpaced the nation’s in 2016’, WBUR, 11 May. Available at: http://www.wbur.org/bostonomix/2017/05/11/massachusetts-2016-gdp (Accessed 26 May 2017).

Tilak, V. (2017). ‘Bay State’s public schools, health care, economy stand out’, US News & World Report, 28 February. Available at: https://www.usnews.com/news/best-states/articles/2017-02-21/bay-states-public-schools-health-care-economy-stand-out (Accessed 24 May 2017).

United States Census Bureau. (2016). QuickFacts: Massachusetts. Available at: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/table/PST045216/25 (Accessed 25 May 2017).

Wang, Y. (2014). ‘State zoning legislation and local adaptation: An evaluation on the implementation of Massachusetts Chapter 40R smart growth legislation’, Master in City Planning, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge.

Wolf, D.A. (2016). Senate passes comprehensive zoning reform: First major update to zoning laws since the 1970s. Massachusetts Senate Press Release. Available at: http://www.apa-ma.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Senate_Press_Release_S-2311_06-09-2016.pdf (Accessed 23 May 2017).

Young, C. (2016). ‘Supporters doubtful new Massachusetts zoning bill will become law’, Walpole Times, 11 June. Available at: http://walpole.wickedlocal.com/news/20160611/supporters-doubtful-new-massachusetts-zoning-bill-will-become-law (Accessed 26 May 2017).

Zollshan, S. (2017). ‘Great Barrington voters to take up changes to solar bylaw’, The Berkshire Eagle, 31 March. Available at: http://www.berkshireeagle.com/stories/great-barrington-voters-to-take-up-changes-to-solar-bylaw,503088 (Accessed 23 May 2017).

[1] Similar to a business improvement district, the provision would permit property owners to pay an additional fee to a non-profit organisation to manage the surrounding area (e.g., for landscaping and sidewalk maintenance).

Discussion

No comments yet.